Why do we use so many alginate fibre sheets in our wound clinic?

The alginate fibre sheet is, without doubt, the most commonly used dressing in our wound clinic. We treat mainly leg ulcers, which are predominantly venous ulcers.

The idea of dedicating a blog post to our favourite dressing came to me during the recent 12th National Symposium on Pressure Ulcers and Chronic Wounds in Valencia (where, by the way, I enjoyed learning and sharing a lot). Many of you asked me about the dressings I usually use and I realized that our star dressing, despite being mentioned in several blog posts, was not the protagonist of any of them.

Before continuing, I would like to stress that the available evidence does not show superiority of any dressing over another in venous ulcers. Writing this entry is an opportunity to share the observations we made in our clinical practice.

Contents

Why is alginate fibre sheet our choice?

To understand this favourite condition, let’s start with some hints about biochemistry.

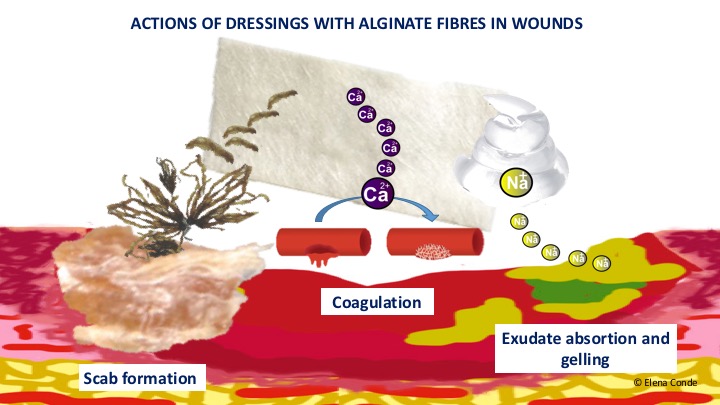

Alginate fibres are natural polysaccharides derived from brown algae (Phaeophyceae), formed by glucuronate and maluronate. These are biodegradable, biocompatible, non-immunogenic, non-toxic and economical biopolymers.1 Alginate has different applications in the textile, food, chemical and pharmaceutical industries due to its ability to form fibres and gels by adding calcium salts or other ions.2 Although this post is dedicated to alginate fibres in sheets or strips, this polymer can also be found among the components of other types of dressings, such as hydrogels. Its beneficial effect on healing, both haemostatic and absorbent, was discovered in the early nineteenth century, thanks to observations made by sailors, who usually used algae to cover their wounds. In fact, this practice of caring for wounds with brown algae was traditionally called “the sailor’s cure”1.

In the present day, alginate fibre dressings are widely used in very exudative wounds, as they have been shown to absorb large amounts of exudate, up to 20 times their weight.

Why do alginate fibre dressings present with absorbent and haemostatic power?

To answer this question, we must use linguistic purism. Although we usually refer to these dressings as “alginate”, the correct name would be “calcium alginate“. And these calcium ions (Ca2+), which are attached to the polysaccharide, are responsible for these two effects of the dressing.

Its high absorption power is due to the fact that the sodium ions (Na2+) present in the exudate are exchanged for calcium ions (Ca2+) from the dressing and, consequently, a sodium alginate gel is formed.2 This gel adapts to the wound surface, conveys growth factors and healing promoting cells, and continues to absorb exudate until it becomes saturated. The physicochemical properties of the formed gel depend on the proportion of glucuronate (G) and manuronate (M) contained in the alginate and the sequence of these carbohydrates in the polymer (consecutive M or G chains, or alternating MG).2 Dressings of alginate fibres rich in glucuronate make more resistant gels.

In our clinical practice, we use alginate sheets as a primary or secondary dressing. We normally cover the alginate sheets with gauze and, given that the absorption is horizontal, in very exudative wounds:

– We apply a 0.1% zinc sulphate solution (we soak compresses in this solution and keep them in the wound and perilesional skin for 10 minutes). See post “Why do we use topical zinc in perilesional wounds and skin?”

– We place several sheets of alginate on top of each other (trying to make sure that the first ones do not exceed the surface of the wound).

– We protect the perilesional skin with a barrier cream.

– We increase the frequency of dressing changes.

The calcium present in the dressing is also responsible for its haemostatic property, as it behaves as a coagulation factor, mainly promoting platelet activation and aggregation.1

When making dressings, other ions can be added to calcium alginate fibres, such as silver, with its consequent antibacterial potential (see post: “Silver in skin wounds“).

What do the studies, guidelines and books say about the use of dressings with calcium alginate fibres?

Systematic reviews designed with the aim of comparing the benefit of different dressings in venous ulcers conclude that there is no evidence to suggest that any dressing is superior to the others in accelerating wound healing.3,4 However, the studies included in these reviews are few and of poor quality. Well-designed studies would therefore be needed to draw conclusions about the real impact of the use of the different wound dressings.

Given this lack of evidence, guidelines usually recommend that the dressing should be selected on the basis of exudate, perilesional skin, frequency of dressing changes, patient preferences and cost-effectiveness.

And what do we find in the books? This is the most frequent list of indications for calcium alginate fibres:

- Slightly bleeding wounds, due to their haemostatic power (e.g. after sharp debridement).

- Very exudative wounds, owing to their absorbent action.

- Wounds with an irregular wound bed, due to their capacity of adaption.

It is always highlighted that the frequency of dressing change will depend on the exudate. It is recommended that alginate fibres should not be used on wounds with little exudate and, if the sheet is dry and adhered to the wound bed, it should be moistened so that it gels and thus avoids a traumatic removal.

What does clinical experience tell us?

Our experience with the use of calcium alginate fibres in our clinics suggests that their interest is not limited to the indications traditionally given in the literature.

We use this dressing in any situation where we want to simulate a “physiological scab” to promote healing. More than one will be surprised by this statement, because many of you will have in mind the axiom: “scabs must always be removed”. Undoubtedly, the scab must be removed if either there is underlying pus when pressing or attempting to move the scab, or the crust is too thick and makes pressure on the wound bed or is easily detached. But wouldn´t acute wounds close with the formation of a scab that ends up coming off on its own, and if we remove it early healing may be delayed? Don’t forget that scabs are deposits of dry exudate and cellular debris that, in the absence of infection, behave like a protective layer that maintains optimal micro environmental conditions for healing.

Now we are going to talk about two applications in which daily clinical observation indicates that calcium alginate fibres are interesting:

- Superficial erosions and ulcers in the context of phlebolinfedema (chronic venous insufficiency and secondary lymphedema). These lesions are usually multiple and very exudative.

We usually apply medium strength corticoid cream on wounds and perilesional skin, covered with alginate, gauze and compressive bandage (See post “Venous insufficiency from a dermatological perspective“). If it is difficult to remove the remains of alginate fibres intermingled with the formed scabs, we leave them and wait till the next dressing change, when they are usually more easily detachable.

- Donor site (See post “Which dressing do I choose to cover the graft donor site?“) and punch graft recipient site (See post: “Types of grafts to cover chronic wounds: which one to choose“).

In the following image I show the evolution of different wounds covered with punch grafts. Normally we space dressing changes 5-7 days. The photos of the upper row correspond to the first dressing changes and those of the lower row to the final stage of scab formation, with almost complete epithelialization.

Although these lesions can be covered with different atraumatic interfaces and alginate as a secondary dressing, experience tells us that alginate as a primary dressing is a good option from day one, since its fibres are intermingled with exudate rich in keratinocytes and growth factors, creating a scab that favours epithelialization. This yellowish-white material should not be removed between the grafts and in areas without optimal attachment. The calcium alginate sheet behaves like a matrix to convey the cells and growth factors that are present in that material. As we can see in the photos, the coloration of the grafts varies according to their attachment (the pinkish-purple ones are the ones that present greater angiogenesis). The success of the procedure lies in spacing dressing changes and cleansing the wound bed as little as possible during those changes so as not to modify the pro-healing microenvironment. Therefore, in cases of grafted wounds, the removal must be especially careful. If fibres remain adhered, we do not remove them and we wait for the formed scabs to come off in the following dressing changes.

In the following image we can see, ex vivo, an unused alginate sheet, a gelled sheet after wetting and the crusty appearance of the dressing after drying. As it is shown in the photos of the alginate sheets on the grafted wound (procedure carried out 7 days before), in order to remove the dressing adhered to the lesion, we moisten it with either faucet water or physiological serum and, once gelled, we can detach it en bloc.

If we use portable negative pressure therapy devices to promote graft attachment in complicated locations or situations (See post: “Punch grafts and negative pressure therapy: a successful couple“), we also tend to cover the grafted lesion with alginate sheets before placing the device.

Although the alginate is the protagonist of this entry, I have also mentioned the other main players in the practice, i.e., punch grafts, topical corticosteroids, negative pressure therapy and, of course, compression therapy.